|

In another letter, Veronica again referred to the problems created by the evacuation and its sometimes unpredictable nature.

“ The evacuee problem has reached an acute stage in which the poor things now arrive bombed, destitute and entirely unheralded with a chit to say billets must be found for them. On return from a rare afternoon out, I found two more had turned up here in my absence without any sort of warning. This brings our complement up to eight in this household.

The latest arrivals here are the heroic family whose house was demolished in Tooting. They came with nothing except the clothes they were wearing. Someone had given them a railway voucher. The government will pay a billeting allowance of 5 shillings a week each and apparently, Providence does the rest. As a result of two year’s hard thinking on the subject of a bombed London, this seems to leave something to be desired.

Any spare time I have is spent in filling up forms in the food and billeting offices at one of the most inaccessible of the Somerset villages, where the rings of the young ady clerks, if real, would buy a couple of Spitfires at least. I am told that the Hastings people are to go back there in six weeks, which seems to put an official limit to the invasion scare. How heart-breaking this exodus is. I never cease to thank God I live in the country and that my roots are dug in deeply enough to make me of some use. A short time ago actually I was lamenting the shortness of work for women!”

Mrs. Lyne also wrote movingly about some of the problems experienced by both evacuees and their host families:

“ We began the week with a meeting to ‘settle the evacuee problems once and for all’, which promptly split up into 10 small meetings of two each and continued until brought to a merciful conclusion by the black-out.

Since then we have continued to struggle exactly as before with the usual reluctant householders; rations; billeting officers; damp babies; identity cards (always lost); rude old maids; the P.A.C. and, as always, that dreadful bogey called “Axbridge”. This is no longer a place to me but Bumbledon and Bureaucracy incarnate bound up tightly in red tape. There is also something much quoted by the evacuees called “the other end” which gave them every promise under the sun and apparently assured them we could perform miracles…..

The week has been remarkably free from evacuee troubles except that the usual trek home has now started. This invariably occurs after about three weeks of rural life. Nothing is going to settle this problem, not even bombing. Families just will not be separated. Though I believe too the question is very largely a financial one; people living on the minimum find it literally impossible to make ends meet when the unit is broken up.

There is also the soul-destroying business of living without roots. The woman wandering about the country roads because she feels she is in the way in her billet naturally thinks of her husband muddling along at home, and fondly pictures him, as we all do, quite unable to get along without her for more than 48 hours. I do wish I could think of a solution.”

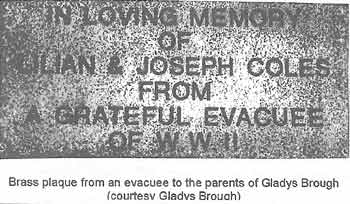

These then are some of the adult recollections of evacuation. Let us now turn to the wartime children of Wrington to get a view of what it was like for them. Gladys Brough and Pam Board were eight years old when the war started. Gladys now takes up the story:

“ What I can remember is all the evacuees that came here. And although we’ve only got three bedrooms, in one room we had two children at the top of the bed and two at the bottom. In another bedroom were my mother and father, and the third bedroom was also full of evacuees, ‘cos we had so many; Reggie Lines, Anita Smith, Doreen and Dennis Silk from Bristol. During the war they used to have a coach out from Bristol that used to come to the [Golden] Lion. They used to put their buses underneath where Mike Thorn has got his house now. They would stay the night to see their children and go back into Bristol the next morning.

The London ones all came to the hall and were put out in different places. Mrs. Annette and Lady Hanson, who were marvellous, organised it all. My sister, who was older than me and lived up the road, had lots of evacuees. She had Charlie and George Tyson and Sid and Dave Warder. She also had a family called Smart, that came out to the Lion from Bristol and Barbara and Joan were the daughters. You didn’t have to worry about them all sleeping together, unlike now, when the kids all want their own room.

In those days, when we went to school, although it’s hard to believe, we all went to school together. All the boys and girls would go up together and call for each other on the way. We were all a bit inhibited until the evacuees came and wouldn’t say boo to a goose. The London ones taught us a few tricks. When they arrived, naturally we were staring and one of the girls said. “ Do you want a photo?” It was all new to us. We got on very well with them and one of them, Joan Tyson, is still our best friend.

Pam’s sister worked in service up at Cowslip Green and there were a couple of evacuees staying there. One of the girls was such a daredevil. She used to have a “sit up and beg” bike and she would have one of the evacuees on her handlebars, another on the back and her on the saddle and she’d come all down Redhill without using her brakes. Another thing she did was to climb up by the chimney-stack and read her book!

We used to go down in Ladywell and we’d try to talk Cockney. I know it was the war but they were wonderful times, absolutely wonderful. We thought they were out of this world. All the ones that came to Wrington all seemed to be happy. The Owers and the Tysons didn’t know each other until they got to Wrington. One family came from Poplar and the other from Kilburn. They were a laugh a minute. Mrs. Owers was proper old Cockney. I can honestly say that I don’t think I ever heard of one evacuee coming to Wrington that didn’t like it.”

|

|

|

|

Both of Olive Mellett’s “boys” have since provided brief written accounts of their happy stay in Wrington . Barry Johnson writes:

“ One day in June, over sixty years ago, I was heading home, after a hard day, from London’s Carlton vale school when, as one of many, I was labelled and loaded onto a bus. The bus took us to Paddington railway station and away we went. We had no idea where.

I remember being taken off the train and loaded into a bus. I remember arriving at what I later learned was Wrington’s Memorial Hall. I remember crowds of kids in the hall. I remember being one of, or even the last kid to be taken out of the hall, carried to a house, late at night, and hearing the occupant saying there was already too many kids in the house. I remember the occupant relenting and taking me in.

In the house of Mr. and Mrs. Millard with their daughters Olive and Lillian I lived for the next five years.

What can I say about the loving care I, and later my sister, received in this home? I can’t say enough. Later, after a visit to see us, my father went off to fight in North Africa. Mum was making ammunition boxes in London. We and thousands of other “Londoners” were being cared for by country folk.

I don’t remember it being difficult adapting to country life. “Dad” Millard was off to Marshall’s farm every morning at some ungodly hour to milk the cows. At least that’s what I think he did. He then walked back to the house for breakfast, after which he walked back to do more than a regular day’s work. The highlight of any visit to the farm was riding on those mammoth sized cart horses. Another highlight was having a spoonful of malt every morning at the school which had been set up in the Memorial Hall. I think that this treat came to an end when we were transferred to the village school. remember lots of things that made my life and that of my sister Ann very comfortable. - as comfortable as it could be in those times of rationing, shortages and other restrictions caused by the war.”

Gordon Bridges has also committed his memories to paper:

“ We are told that the evacuation of schoolchildren from London went without a hitch! The children, smiling and cheerful, left their parents to board trains for unknown destinations in the spirit of going on a great adventure.

Allowing that wishful thinking, one of the earliest schools to start the evacuation was my old infant school Carlton Vale. Forty children aged between four and seven assembled before dawn; each child carried a gas mask, food and change of clothing and wore three labels.

Arriving at Paddington Station, a teacher cheerily told my mother “We’ll be back in a week; the weather’s glorious for a nice holiday.” However, I was still an evacuee three years later. The organisation at the station was good and quite quickly we left for the West Country.

The journey lasted a long time, too long for some, namely those who wanted their parents, those who wanted to be sick, and finally those who wanted to run riot. Controlling us were two teachers from our school, two ladies determined to continue our education, wherever the Education Board decided that would be.

Upon our arrival at Weston, we the Carlton Vale infants contingent were taken to a village called Wrington. Being five at the time my only recollection of the first evening of my stay with the family of Mr. and Mrs. Oliver Millard and their daughters Lillian and Olive was a hot drink and a warm comfortable bed.

The daughters were put in charge of me and two other evacuees Barry and Ann Johnson, who overnight became my brother and sister. Wrington Somerset was a very unusual place indeed, for it produced instant new families.

School was one side of a curtain that divided the Memorial Hall that was until a few weeks later when we were allowed to attend the village school. On the journey to school each day I had to pass Sullivan’s Bakery, the window of which even in wartime was attractively decorated with what appeared to be cream cakes. As luck would have it Mrs. Sullivan thought I looked like a nephew of hers, therefore the trip to school took a little longer each day as I made sure Mrs. Sullivan saw me, for having seen me, a cake was always given and gratefully received.

I have many fond memories of the village and on my return visits; I always feel that I have come home.

So my evacuation turned out fine, I was treated as a member of a wonderful family and given love and affection, which secured friendships to last a lifetime. For some of us it was a life-enhancing, mind-broadening experience, leaving us with memories we treasure to this day. - namely the generosity of those who took us into their homes.”

It was not just Londoners who sought shelter in the village; there were also temporary visitors from much closer. When Bristol began to attract the attention of the Luftwaffe, people were bussed out to Wrington just for the night, until the all clear was given. Olive Mellett recalled some of the details:

“ When Bristol got bombed people came out every night in coach loads from Bristol and slept in the British Restaurant [The skittle alley of the Golden Lion]. There was a couple who tried to start up a concert party with them but it was too erratic. But it gave us something to do. When Bristol was bombed we also had a woman, Gertie Baker, and her three children with us for eleven months, in addition to Barry, Gordon and Ann. They went in the empty bedroom. They offered you a fold-up camp-bed if you said you hadn’t got any room.

Gertie slept in the double bed with her two girls, with Teddie on the camp bed. They each had their own ration books and for our own evacuees, we had eight shillings a week for each of them, which covered our costs. We got on exceptionally well and are friends to this day with the Baker children. They moved out later to a house in the West Hay Road and stayed there for about four or five years.”

Many of the evacuees came to Wrington from East London; some of them liked it so much that they have stayed here ever since. The Village Journal of June 1978, under its regular “Personality of the Month” feature, carried an item on Frederick and Rebecca Owers, whose family of eight children were all evacuated to Wrington. Several of them still live here.

Trixie Kirk, who with her husband ran the fish and chip shop in Station Road during the war, vividly recalls the children’s arrival by coach, and how they stood in the Memorial Hall, each with a carrier bag of possessions, forlorn and homesick, awaiting their fate.

Eileen Owers (now Schroeder), who was the only girl in the family, explained that her mum and brothers came down before she did because at the time she was having a holiday with her parents’ friends in Kent. When the evacuation came her mum wouldn’t let her children go without her and Eileen was brought down later by her father.

When children arrived singly, or in pairs, it was relatively easy for the billeting officers to find suitable homes for them. With a family the size of the Owers’, especially when that family included seven little boys, the outlook was considerably bleaker. Such a large group would almost inevitably be split up. It is hard to imagine how lonely and frightened the children must have felt if they were separated from siblings – their sole connection with the life and surroundings from which they had suddenly been torn away.

Eileen and her brothers were lucky. The kindly Diana Anson, on seeing the family left behind once all the other children had been dispersed, agreed to accommodate them all at her large home at West Hay. Eileen provides the detail:

“ Mrs. Anson took the two largest families of the evacuees that came and she very kindly accommodated mum and the boys and they had the nursery at West Hay. There was another family – Mrs. Simpson and her boys, so we shared the nursery between us. When dad brought me down we walked all the way from the station at Yatton to Wrington. I was about 9½ and stayed with the chauffeur and his wife, Mr. and Mrs. Markwell, in West Hay Cottage, until I was sixteen. Unfortunately, I couldn’t stay with the boys because a girl had to have a separate bedroom.”

According to Eileen’s brother Dennis, they lived very well at West Hay and he retains very fond memories of the Ansons’ many kindnesses:

“ The cook used to come up on a Sunday morning and bring us up a jam tart for a treat and Mrs. Anson let us have skimmed milk from the cows. They were self-sufficient for food. They had a large storeroom – stone cold it was – where they used to keep eggs they had bottled in great big dustbins. When we used to go in there you could see all the dead pheasants lined up for the maggots to come out of them.

They also had all the meat hanging up and in another room they had all their wines and spirits. They used to put a table tennis table in the large dining-rrom and we’d play with her two sons. Every Christmas time they used to put on a party for us and the butlers and staff. The staff and us didn’t do a thing and everybody had a present from Mrs. Anson. They had a huge Christmas tree and they used to wait on all of us in that big dining-room.

When they had dinner parties we used to stand on the balcony and watch them going into dinner with their evening clothes on. On one occasion there were British troops marching along West Hay Road and they wanted to take a break so they came in onto Mrs. Anson’s lawn. She fed them and gave them tea and we spoke to them and asked to have a look at their guns. I can also remember big American lorries coming along there, because they had a base near Cleeve and even tanks came through Silver Street once. We went out there and said “Any gum, chum?” which was the saying we used, and a couple of them gave us some.

Eileen still has a necklace given to her by Mrs. Anson’s daughter, Valerie. She used to take us boys out in the large Morris car for a walk over the Mendips. We also used to ride horses up there. She joined the army and rose to the rank of Major. One Sunday she even came to inspect the Home Guard in the Memorial Hall yard.

When we went to Wrington School we weren’t really accepted for a long time because we were evacuees. Some of the local lads used to have gang warfare on us along West Hay Road, throwing stones and goodness knows what. This only went on for about a month until they got used to us and after that we were the best of friends.

The Headmaster at the time, Mr. Bisgrove, used to let us go home for lunch a little bit earlier, to overcome that. Towards the tail end of the war we used to walk down from the school to the British Restaurant for our dinner

Coming from London, we were fascinated by the animals. We always thought that if we went in a field they’d start chasing us. If there was a load of cows we’d say, “ There’s a bull – let’s get out – you’re not wearing nothing red and things like that. Then Eileen met Ken, who was working on a farm and he put us straight on all these things.

I can remember that one day one of the Anson’s horses was in trouble. They couldn’t get her better and dad heard all this rumpus from the stables around midnight, which woke us all up. So dad went downstairs and asked Mrs. Anson if there was anything he could do. She said that she didn’t think he could and that they couldn’t get a vet. So dad went down and had a look at her and he put that horse right. He had his own horses as a haulage subcontractor to people like the Co-op and the brewery. He stayed with the horse all night and next morning it was one hundred percent better – he saved its life and they could never thank my father enough for it.

When we were at school the local lads told us there were some railway trucks at Burrington station with a load of goodies in them. So we went up with them. They had all these square carriages and one of the local boys got in and found all these American helmets – they came down over our ears. They were handing them out and I can remember having a white one – an M.P.’s one. We were trying to dodge the guards, who reported us to the school, so we had to all take them back. In exchange we got a couple of detentions for our trouble.”

The Owers family never went back to London. Their home was bombed, Mr. Owers lost his animals and they stayed in Somerset after the war.

When Lady Anson died in May 1976, a glowing tribute to her appeared in the Village Journal. Talking of her care of evacuees, the writer said that it was typical of her that she was the first to welcome two of the families into her own home.

Two months later in the same publication, Doris Rendell, Axbridge Rural District WRVS Centre organiser, wrote:

“ Di Anson joined W.R.V.S. in 1939, at the time of the formation of our Service, and took part in nearly every branch of our work until shortly before her death. In addition to her fine work locally, she gave outstanding service as a member of our “Queen’s Messenger Service”, when we took supplies of food and water after the heavy raids on Plymouth, Bath and Bristol and gave what help we could to the suffering.

I must testify to Di Anson’s courage and friendliness for all, through all those horrors. Also to the readiness with which she answered “call-outs”, even to turning out with a towel over her head, because she had been washing her hair at the time of the call! In addition, when we were asked for volunteers to relieve our London members, driving supplies in support of rescue workers during the Flying Bomb attacks on London, Di took on two spells of work…For Di Anson, love and care for others quite surpassed all personal fears.”

|

|

|